The Mamas & the Papas were a popular band formed in the late 1960's, known for their Billboard hits "Monday, Monday" and "California Dreamin'". They are frequently categorized by music historians under the "sunshine pop" genre, which "originated in California and typified by rich harmony vocals, lush orchestrations, and relentless good cheer." (allmusic.com) Also found under this categorization are groups like the Beach Boys and The Byrds, as well as frequent comparisons to other co-ed harmony groups like Spanky & Our Gang and Peter, Paul, & Mary. But while other typified California bands like the Beach Boys were singing about girls and surfing, and other folk blends like Peter, Paul, & Mary confronted political upheaval, The Mamas & The Papas addressed complex issues of romantic doubt. By subverting the tradition of romance by addressing themes of possession, selfishness, and mistrust while shedding light on the complications of normative monogamy The Mamas & The Papas created a definitively radical sound. I argue that The Mamas & The Papas did not signify the stereotypical 1960's "sunshine pop" optimism, instead heralding the passive cynicism and introspective self-reflexivity of the 1970's "Me decade".

In American media, radical portrayals of romance didn't begin emerging until the 1970's. When the people witnessed the atrocious mistake of Vietnam, the dizzying chaos of president John F. Kennedy's assassination, as well as a rise in the feminist revolution via birth control, the collective consciousness began to take a turn towards cynicism and irony. Ideas of commitment and monogamy began to come into question. As Tamar McDonald's evaluation of radical romance in her book "Romantic Comedy" states, artistic interpretation of romance during this era "is often willing to abandon the emphasis on making sure the couple ends up together regardless of the likelihood, instead striving to interrogate the ideology of romance." (p. 59) McDonald is reflecting on society's collective mistrust in the established systems on the early 1970s, and artistic media's reflection on it. Yet it was early on, in 1965, that The Mamas and the Papas first album, "If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears", focused heavily on the tenuous nature of commitment. Lyrics like "I got a feelin' that you're stealin'/all the love I thought I was giving to you," from "Got a Feelin'" express the radical themes established early in their career. While other popular bands of the time were singing "Love, love, love" , The Mamas & The Papas were wondering "Baby are you holding/holding anything but me?" and if "Monday evenin' you would still be here with me"? The Mamas & The Papas rarely sang about successful love. And when they did, it was by covering existing songs like "My Girl", or standards like "Right Somebody to Love", performed as childishly by Michelle Phillips as Shirley Temple, who earlier popularized the tune.

Not only did The Mamas and the Papas completely abandon any emphasis on "making sure the couple ends up together", when they did flirt with the idea, it had to be done through ironic, childishly mocking tones. This is also in keeping with the tone of "cynical apathy" (p. 61) that McDonald believes was spawned by the social upheaval of the 1960's and was represented in the radical romance films of the 1970's.

When discussing the unique radical tone of their music, it is worth noting McDonald's point that "the idea that romance and satisfaction could be opposite values is new to [this genre]". If the idea of opposing romance and satisfaction is a marker of the radicalization of romance, then The Mamas and the Papas can now be put forever in the books as a definitive precursor. Their self-titled second album and third album, "Deliver", mutated the radically romantic themes of unfaithfulness and mistrust into a bitter anger and sadness. The lyrics and tone of these albums are an emotional reaction to the to the painfully unsatisfied attempts at uncertain love from the first album. Their lyrics are heavily peppered throughout their discography with terms like "lie", "cry", "should/shouldn't", "could/couldn't". The Mamas & The Papas have stopped wondering where their lovers have gone and if they'll return and are gleefully chanting "I can't wait/to say goodbye/I can't wait/to make you cry". The heartbreakingly complex "Did you Ever Want to Cry?" speaks from the perspective of a jilted lover resentfully observing her ex-lover being hurt by another woman.

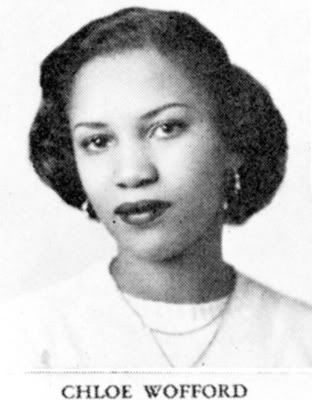

The Mamas and The Papas music focused so entirely on the radically romantic ideas of dissatisfaction in romance and the unlikelihood of love everlasting that it is only logical to assume they were singing from personal experience. Indeed, it is admitted through many personal accounts and documentaries that there was a string of betrayals amongst them. Lead guitarist John Phillips was married to singer Michelle Phillips, but this did not prevent lead guitarist and best friend Denny Doherty from beginning an affair with Michelle. This was also in spite of the romantic longings that lead singer Cass Elliot had for Denny. As the band sang about each other, to each other, through intricate harmonies that relied on cooperation, the self-reference became dizzying. This aspect of their music also contributes to their radical post-modern categorization, because as McDonald says, "the major thematic concerns of the radical romance all derive from issues of self-reflexivity." (McDonald, p. 67) We also read the thoughts of many cultural anthropologists on the subject of post-modernism in the text "Cultural Studies" by Chris Barker. As noted by people like Gergen, Williams, and Giddens, post-modern culture engages in self-reflexivity, "a discourse about experience." (Barker, p. 201) This 'structure of feeling' (Barker, p .200) exhibits "paradox, ambiguity, uncertainty" (Barker p. 341). The heated, short-spanning career of The Mamas and The Papas, coupled with the obsessive themes of distrust and unfaithfulness, accusation and apology, are too prevalent to not be self-referential .

The Mamas and Papas exemplified the self-involved theme of the 1970's 'Me Decade', as also seen in other radical romantic texts of the time like "Annie Hall" (1977). As McDonald notes in her analysis of romantic comedies, "...optimism and the belief in possibility of change have become anachronisms, and that the new decade [the 1970's] demands introspection." (p.61) The Mamas & the Papas certainly did dwell on their own personal woes, expressing them through their music. In 'Creeque Alley', they sing about their group's origins and struggles getting to California, their main chorus nothing that "Nobody's gettin' fat/except Mama Cass." They did not suspend their internal conflicts to address the widespread political issues or civil rights conflicts, like many other folk bands of the era- they spent every ounce of energy obsessing over their own existence. "I Saw Her Again" is a quintessential picture of self-involvement.

Here we get a true idea of the complicated genius The Mamas & The Papas were able to express. "I'm in way over my head/ Now she thinks that I love her/ Because that's what I said/ though I never think of her." Not only does he lie by telling this girl that he loves her, but he disregards his deception: "But what can I do?/I'm lonely too/and it makes me feel so good to know/She'll never leave me." Given the knowledge of the complicated betrayals that occurred amongst the band members, the interlocking harmonies that relied upon one another for expression as they sang about each other, to each other, creates a new dimension of self-reflexivity.

The multiplying mirrored layers of self-reference and frank, painfully honest doubt about the social construction of love and romance sets The Mamas & Papas far from the stage of other bands of their era. But they were able to plant their dark seeds in an uplifting, nostalgically folksy style that catapulted their internal strife up the charts for two short, burning hot years. Though they are remembered as a "sunshine pop" group, their legacy lies in their radical roots.

WORKS CITED

1. Eder, Bruce. "The Mamas & The Papas." AllMusic. 2010. Web. 13 Nov. 2010.

2. McDonald, Tamar Jeffers. "Romantic Comedy and Genre." Romantic Comedy: Boy Meets Girl Meets Genre. London: Wallflower, 2007. Print.

3. 1. Barker, Chris. "Enter Postmodernism." "Television, Texts, and Audiences." Cultural Studies Theory and Practice. Los Angeles: SAGE, 2008. Print.

4. Annie Hall. Dir. Woody Allen. Perf. Woody Allen, Diane Keaton. MGM, 1977. DVD.