As I will soon detail, modern culture work is focused on pinpointing the balance between both societal influence and biological determinism when analyzing today’s post-modern identities. And, as both culture and science rapidly hybridize with technology, I believe a cinematic trend has emerged. As self-reflexive, post-modern audiences cope with the complexities of the societal, technological, and biological influences on their existence, filmmakers address the intricate controversy by essentializing the inexpressible human condition. I will be using cultural studies to explore modern depictions of hypothetical futures in science-fiction cinema affected by population control, artificial intelligence and biological hybridization, as well as betrayal by the system to determine essential, normative, but autogenous ideals of self-sacrifice and cooperation.

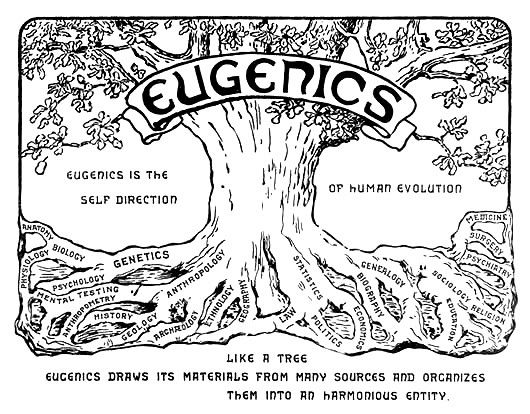

EUGENICS:POPULATION/CONTROL

Our culture is fast approaching the end of the border of science-fiction and tumbling into a scientific reality. Our culture is rationalizing and measuring like never before, grasping at strands of meaning as mainstream religions continue to fail the changes of post-modern society. Bryan Turner dubs this the “somatic society,... in which a ‘major political and personal problems are both problematized within the body and expressed through it” (Barker, 118). Aptly named for the sedating affects of the widely distributed tranquilizer in Aldous Huxley’s future of ‘A Brave New World’, the concept of a ‘somatic society’ addresses the nature of sociobiology and genetic determinism, as seen in films like ‘Gattaca’ and ‘Equilibrium’.

Sociobiology is a branch of biological sciences that explores the biological evolution of a society and the socialized individuals within that society. As explained by Edward O. Wilson in his paper titled “Heredity”, humans have a social structure that cannot be mistaken for the patterns of insects or reptiles. For example, we are comprised of small social circles and long childhoods of maternal reliance. Wilson cites the 1945 research of anthropologist George P. Murdock, who listed the recorded characteristics of “every culture known to history and ethnography:

Age-grading, athletic sports, bodily adornment, calendar, cleanliness training, community organization, cooking, cooperative labor, cosmology, courtship, dancing, decorative art, divination, division of labor, dream interpretation, education, eschatology, ethics, ethno-botany, etiquette, faith healing, family feasting, fire making, folklore, food taboos, funeral rites, games, gestures, gift giving, government, greetings, hair styles, hospitality, housing, hygiene, incest taboos, inheritance rules, joking, kin groups, kinship nomenclature, language, law, luck superstitions, magic, marriage, mealtimes, medicine, obstetrics, penal sanctions, personal names, population policy, postnatal care, pregnancy usages, property rights, propitiation of supernatural beings, puberty customs, religious ritual, residence rules, sexual restrictions, soul concepts, status differentiation, surgery, tool making, trade, visiting, weaving, and weather control.” (Wilson, 1978:15)

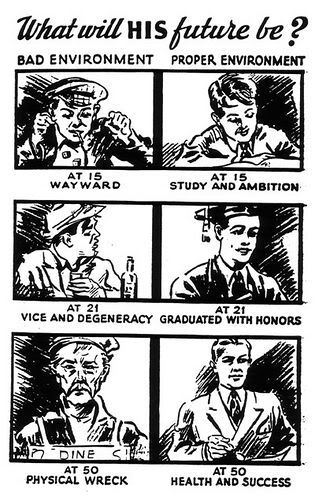

Although there are some irrefutable observations that sociobiology determines, not all aspects of the study find consensus- especially amongst sociologists and culturalists who believe that these findings are biologically reductionist, “that there are invariant features of human genetic endowment that are resistant to change.” (Barker, 112) The idea that a rigid science could impose limitations on our free-will and agency can be offensive to a post-modern society that practices self-awareness, and to a lesser degree, self-improvement. However, science and culture are inextricably linked. Barker remarks in the book ‘Cultural Studies’ that “culture forms an environment for the human body and feeds into evolutionary change. Hence, environmental change, which includes the social and cultural aspects of human life, can change biological development outcomes” (113). We are coming to see the fruition of this understanding, and science is gently being urged towards the manipulation of DNA to improve human lifespan.

In the film ‘Gattaca’(1997), the main character, Vincent, is a naturally born man in a world of where genetic pre-determinations can be made in utero to emphasize the strongest genetic material possible during your development. Therefore, when Vincent tries to pursue a career as an astronaut, he is discriminated against for being ‘genetically inferior’. Through this film, we begin to see the dangers of this biologial reductionism. Once we begin to assign definitions and values to the flesh, we can more easily discern and ascribe material value to a personhood, and thus, an identity.

Vincent is forced to “borrow” the identity of a genetically superior person who has been crippled. They lend him DNA samples so that he may pass all the various physical exams to qualify for the high-ranking position he seeks. This is a portrayal of a hypothetical near future, but Barker is already recognizing the consequences in today’s society: “Biological reductionism...has [made it] apparent that ill heath is distributed differentially by age, class, gender, place, etc” (122).

This sort of future is nearly upon us- the use of enacting ‘disciplinary bodies’, that is, according to philosopher Michel Foucault, “the mechanism of ‘policing’ societies by which a population can be categorized and ordered into manageable groups” (Barker, 121). To differentiate and value individuals based on their health is already in motion through modern insurance systems, and easy to conceptualize through Gattaca.

Another film that utilizes the control of biology is the 2002 film ‘Equilibrium’. In this fictional society, the film’s main character, John, is a high-ranking government official that participates in the location and execution of ‘sense offenders’. ‘Sense offenders’ are people who choose not to submit to the mandatory government instilled mood equalizers. The tranquilizers negate all emotions of sympathy and compassion, which also removes many of the loving activities noted by George Murdock above. When John misses a dose of the drug, he begins to feel natural emotions again continues neglecting the drug.

Barker notes an important point about the nature of chemical emotions: “Though emotions are culturally mediated, the sharing of broad emotional reactions is one of the features that forge us together as human beings. We all feel fear and we all have the potential to love” (128). Both ‘Gattaca’ and ‘Equilibrium’ work to recognize the innate, essential qualities of humanity to practice self-sacrifice and compassion. In the case of Gattaca, we see the people around Vincent sacrificing their adherence to the system to see someone who has already lived past science’s projections to fulfill a dream. Even when using science as its foundation, society cannot measure an innate aspect of human survival. In Gattaca, the preference for emotion and sensual indulgence is portrayed. We also see the stark contrast of immediate compassion when compared with the gray emotionless world that surround the ‘sense offenders’. John, without being surrounded by a culture of compassion nor being taught the nature of compassion immediately falls into the practice of doing so, regardless. This films works to illustrate evolutionary biology’s suggestion that there is a high “likelihood that there are cultural universals.” (Barker, 128)

A.I.:ARTIFICIAL/IDENTITY

Science-fiction uses artificiality and the construction of an identity to highlight the binary relationship to humans. In a Saussurian sense, knowing the artificial interpretation of technology gives us insight into what actual humanity is. Science-fiction enables the exploration of identity and reality by fully constructing artificial versions of them and asking audiences what the essential differences are.

It has been suggested that the advent of technology has pushed the concept of a self-identity to the forefront. “For Elias, the very concept of ‘I’ as a self-aware object is a modern western conception that emerged out of science and the ‘Age of Reason’. People in other cultures do not always share the individualistic sense of uniqueness and self-consciousness that is widespread in western societies.” (Barker, 216) According to Stuart Hall, this is an example of western society as an ‘enlightened subject’, which is “based on a conception of the human person as a fully centered, unified individual, endowed with the capacities of reason, consciousness, and action, whose ‘centre’ consisted of an inner core...The essential centre of the self was a person’s identity. ” (Barker, 219)

In science-fiction, audiences are exposed to concepts like these and then allowed to see the theoretical implications of living in the world we are watching ourselves create. Humans create machines to instill convenience in their lives, offloading monotonous tasks. In these fictions, we see the machines get increasingly more sophisticated in function. In ‘Blade Runner’ (1982), the androids, known as ‘replicants’, were off-world slaves. ‘The Matrix’ (1999) repeats this theme as indentured robot slaves rebel against their human oppressors. In ‘Terminator’ (1984), the Skynet networking system became self-aware and initiates a nuclear holocaust on the humans.

In the case of ‘Blade Runner’, replicants are made entirely in the human image. They are capable of intelligent language and signification. They are capable of highly complicated, self-aware reasoning skills, enough to create their own agency and rebel against their creators. A bounty hunter, Dekkert, is hired to retrieve a band of runaway replicants, and in the process falls in love with one. How can the post-modern, self-aware audience account for the difference between a real human self and an other made in the image of our selves? Through enlightenment and reason, it would seem that for all intents and purposes the replicants have become free agents, and thus, human. Audiences are capable of making these associations because of the sympathetic, essentially human characteristics of affection witnessed between Dekkert and the replicant.

A different perspective causes rationality to again tug at our conception of identity. Returning to ‘The Matrix’ and ‘Terminator’, we see that these artificial intelligences are just as self-aware and capable of rationalization. They have agency and motivation as many culturalists note as the key to identity. By chance of unintended evolution, these robots are also capable of sociological selves formed in relation to their environment (Barker, 220), triggered by some sort of arrangement of complex computations or even faulty programming. But we do not give them as much empathy or credit. The only discernible difference is the lack of compassion, the pure hatred and destruction that seems to be the aim of these films’ post-war machines. If we understand these androids to define humanity by acting as their binary, we again see that science-fiction is defining humanity as essentially altruistic, instinctively drawn to a sense of justice and peace.

MECH/FLESH

Science-fiction also explores our attempts to circumvent the flesh, to reject the socio-biological implications that our weaknesses insist upon. As in reality, these films will instill elaborate virtual realities for characters to indulge in so that they may avoid their real-life identity.

Sociologist Sherry Turkle examines the fragmented nature of our acculturation in comparison to the “conditions of postmodern multiple identities...the idea of multiple identities refers to the way people take on different and potentially contradictory identifications at varied times and places.” (Barker, 361) Films like Strange Days and the Matrix take the concept of being able to choose which aspects of your identity you are most comfortable with and allowing you to choose them, all the time. In The Matrix, people who exist under the false pretense of reality as we know it are given the option of remaining before finding out the bleak truth that they are actually living in a construction. Their fundamental choice is to accept all aspects of their existence, of their influences and their selves, or to live in a dream world that offers them a false sense of security.

In Strange Days, there is an underground activity in which you can purchase someone else’s memories and physically experience the sensations of their past. This has the consequences of not only just repeating the same good memories over and over again, never to have another original moment, but also the exploitation of someone else’s history.

Both of these films offer their hypothetical populations an attractive virtual alternative. But as Turkle points out of players and their game-lives, the false reality “merely highlight[s] the limitations and inadequacies of their ‘real life’.”(Barker, 362) Again, we see the Saussurian binaries at work- the quality of real-life and the experience of the flesh creates an essential argument to confront and maintain humanity, even in troubled times.

PREPARATION:PRE/APOCALYPSE

After we’ve controlled our genetics and chemicals with science, after we’ve attempted to replace our reality or simply construct extensions to make it easier, after we’ve exhausted our resources and technology, science-fiction is still capable of showing us what human potential is made of. Post-apocalyptic films set in a future where technologies have been destroyed are an interesting study in how our culture would survive, adapting to the conditions of history while recovering from the future. Although mankind was incapable of preventing its mass self-destruction (always self), something inherent lives on.

‘Day of the Dead’ (1985) addresses a group of scientists and soldiers trapped in an underground military base after a widespread outbreak of zombie plague. After attempting to cure, socialize, and kill the zombie population, it is realized that it is pointless to fight against. The main characters ultimately find their peace when they decide to enjoy what lives they have left building a small community together, nurturing the cooperative instincts that ensured our survival in the first place.

‘The Road’ by Cormac McCarthy simply but gently tells the story of a father and his son trying to find relief from the bleak and barren landscape of cannibals and pillagers. All along the way, the father motivates the son to continue on with the explanation that they are “the good guys” who “carry the fire”. There is nothing else in the world to grasp, and yet the will to survive is expressed as the most worthwhile when honoring the most difficult aspects of humanity, self-sacrifice and compassion.

These modern day depictions of the future, sometimes near, sometimes distant, are useful for analyzing what people today believe about the destiny of our culture. While the post-modern self-reflexivity of these tellings could only mean that we are acknowledging our eventual destruction, I believe it is speaking more to that ingrained sense of indefinable, essential humanity.

Works Cited

Barker, Chris. "Biology And Culture, A New World Disorder?, Issues of Subjectivity and Identity, Digital Media Culture,." Cultural Studies. Los Angeles: SAGE, 2008. Print.

Wilson, Edward O. "Heredity." On Human Nature. Harvard UP, 1978. 15-25. Print.

Blade Runner. Dir. Ridley Scott. Prod. Ridley Scott and Hampton Francher. By Hampton Francher and David Webb Peoples. Perf. Harrison Ford, Rutger Hauer, and Sean Young. Warner Bros., 1982.

Children of Men. Dir. Alfonso Cuaron. Perf. Clive Owen and Julianne Moore. Universal Pictures, 2006. DVD.

Equilibrium. Dir. Kurt Wimmer. Perf. Christian Bale and Sean Bean. Dimenson Films, 2002. DVD.

Gattaca. Dir. Andrew Niccol. Perf. Ethan Hawke and Uma Thurman. Columbia Pictures, 1997. DVD.

Mad Max. Dir. George Miller. Perf. Mel Gibson. Kennedy Miller Productions, 1979. DVD.

The Matrix. Dir. Andy Wachowski and Larry Wachowski. Perf. Keanu Reeves and Carrie-Anne Moss. Village Roadshow Pictures, 1999. DVD.

Day of the Dead. Dir. George A. Romero. Perf. Lori Cardille and Terry Alexander. Dead Films Inc., 1985. DVD.

McCarthy, Cormac (2006). The Road. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Strange Days. Dir. Kathryn Bigelow. Perf. Ralph Fiennes and Angela Bassett. Twentieth Century Fox, 1995. DVD.

No comments:

Post a Comment